Credit: Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

Doctors on the front lines of the COVID-19 crisis describe an unprecedented health emergency that has exposed the societal wounds among the poor and people of color that have persisted for centuries.

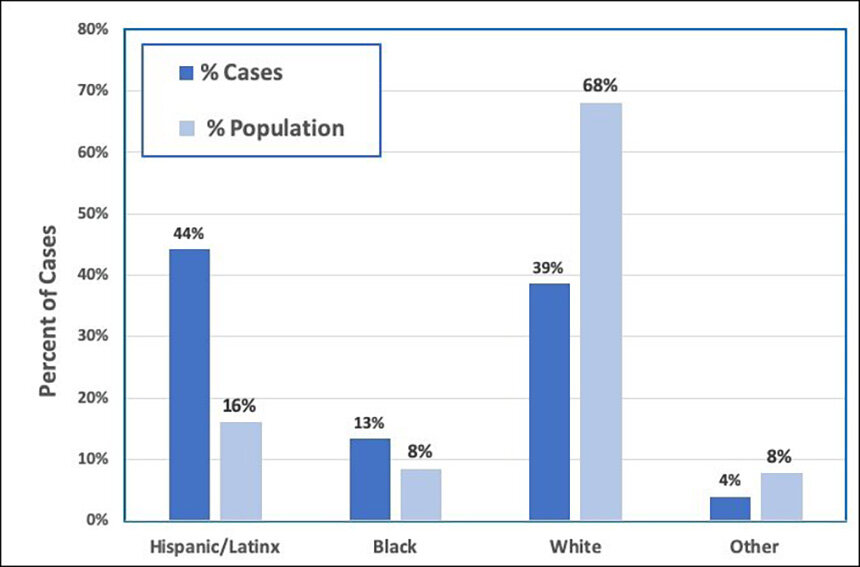

The numbers show the coronavirus hitting the Hispanic/Latinx population more severely than others, accounting for 44 percent of all Rhode Island cases from a group representing only 16 percent of the state’s population. The contraction rate is almost three times the percentage of Hispanic/Latinx living here. For blacks, the number is 1.6 times, or 60 percent higher than it should be.

Whites, meanwhile, account for 68 percent of the population but only 39 percent of COVID-19 cases, according to the Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH).

Health experts blame the lopsided infection rate on crowded living and working conditions. Individuals from these groups also dominate the so-called “frontline jobs,” such as health-care workers, delivery drivers, grocery store clerks, and factory workers — the vocations needed to keep society functioning during a pandemic.

Many of these frontline workers are young adults, which is reflected in the relatively low mortality rate. But these vital, often underpaid laborers bring the virus home or into social settings within densely populated neighborhoods. Sections of Providence, Pawtucket, and Central Falls have the highest infection rates in the state, some higher than much-publicized COVID-19 hot spots like Bronx, N.Y.

Gov. Gina Raimondo, like other governors, unintentionally set this perilous dynamic in motion when she issued a necessary statewide stay-at-home order, while employees within these crucial industries stayed on the job. This policy, however, allowed the more affluent and mostly white population to shelter in their less-crowded homes and neighborhoods.

The shadow economy of people of color and the poor, Brown University professor Lundy Braun said, “labor and sicken in disproportionate numbers to protect others.”

“In other words, people could not have stayed at home had there not been a reserve labor force, a labor force that can barely feed or house their own families that overnight went from a perpetual state of unemployment, and utter invisibility to being essential workers,” she said.

It’s not a new scenario. The oppressive structure revealed by this public-health crisis has deep roots in past diseases and research trials. More recently, racism, xenophobia, and homophobia were revealed during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic in 2003, the Ebola epidemic in 2013, and the HIV/AIDS crisis that stigmatized certain groups for decades.

“No matter time and place, blame has been attached to infectious diseases — usually blame directed by the affluent classes towards the poor, and especially in the United States, the racialized,” Braun said. “And there is lots of blame and judgment to go around with COVID-19, such as the legacy and persistence of white supremacy, a gutted public-health infrastructure, and the militarization of society.”

Risk inequality

Braun, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and Africana studies, and six Rhode Island physicians with connections to Brown University’s Alpert Medical School discussed medical racism and COVID-19 during a May 5 online forum hosted by the Race, Medicine, and Social Justice Working Group at the Brown Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice.

These health-care professionals recounted their experiences treating COVID-19 patients at local hospitals and health centers. They concluded that an inordinate number of people of color lack primary-care physicians and avoid medical help for fear of losing their jobs or being deported.

“We have to essentially call it what it is. Patients may not be coming to see us and are dying at home because of racism,” said Taneisha Wilson, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Alpert Medical School.

Carla Moreira, an assistant professor and vascular surgeon at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, said it’s not accurate to call the response to the emergency a united struggle against a shared threat. Divisions exist because injustices and inequities persist from the country’s failed attempts to confront its past atrocities and systemic racism.

She said appealing to compassion and people’s hearts hasn’t succeeded in making progress with marginalized communities.

“That’s the maddening part because those lessons are there,” Moreira said. “There’s no excuse anymore in terms of not having the ability to learn those lessons and have these conversations. The problem is the lack of leadership and the will for us to sit down and have those difficult national discussions, and it has to go back to having a reckoning with slavery and what happened with Native Americans and all these issues and how we interact in the system.”

Although it didn’t make lasting headlines in the mainstream media, the suggestion made by French doctors in April that COVID-19 vaccine testing take place in Africa sparked outrage within communities of color. The suggestion that the continent serve as a laboratory because of a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) served as a chilling reminder of past medical atrocities, such as the Tuskegee syphilis study performed on African-Americans between 1932 and 1972.

“Until we have those conversations and reckon with those histories, we are going to be bound to repeat them,” Moreira said.

Joseph Diaz, associate professor and associate dean for diversity and multicultural affairs at Alpert Medical School, noted the similarities between census maps that identify the concentrations of cardiovascular disease and hypertension and maps showing COVID-19 hot spots in Rhode Island.

“These are inequities that have been existing for a long time,” he said. “It’s the structures that are set up in society that creates these inequities. So it's not a surprise that this is happening.”

Medical racism

Two types of patients are emerging: those who can afford medical care and marginalized people with low-paying jobs that don’t offer health insurance. The latter typically lack stable homes to self-isolate. Some get paid under the table and, thus, don’t qualify for temporary disability insurance.

“These are the folks who have been really made invisible,” said Catherine Trimbur, assistant professor of medicine at Alpert Medical School. “These are the vulnerabilities and the inequities that have really been structurally ingrained in our society and we continue to allow these things to exist.”

Cyril O. Burke III, a neurologist and staff physician at The Miriam Hospital, noted the institutional bias of medicine, such as rules governing ambulance districts that send poor and minority patients to inferior hospitals while those with wealth get better access to physicians and facilities.

The hierarchical structure within hospitals and medical facilities discourages racially diverse viewpoints, Burke explained.

“Frequently, as the only black physician in the room, you get no backup,” he said. “The people who are most vocal are the people who would challenge you. So if you raise an issue you get challenged often right away and then that’s the end of it.”

The physicians noted that some progress is being made to address medical racism. Alpert Medical School has a committee to identity cultural and ethnic biases in medicine. Nurses and doctors are encouraged to call out inequities they encounter when providing care to their patients.

Diaz suggested changing the compensation structure so that doctors and nurses are paid to improve equity in health care.

“If money is driving everything, let’s see if we can get some incentives to have more equitable health care,” he said.

Burke described the challenges of changing convention. Court decisions that mandate social change often lead to new forms of racism, such as Brown v. Board of Education, which banned school segregation in 1954. Yet, racial and economic divides in education are as stark as ever.

“What physicians can do is talk about the possibilities, what is reasonable, and what can be done. But it’s very hard within this system,” Burke said. “But the public is going to have to want something because it's the elected leaders that do it.”

Trimbur said society needs “to acknowledge that we need to build the trust of communities.”

Moreira noted that, ”If we continue to do the same things we are going to be back here in a couple of years.”

A second wave

As stay-at-home orders are eased and the economy reopened, there is concern about making a bad situation worse within marginalized communities. Michael Fine, a health policy advisor for the city of Central Falls and a former DOH director, worries that the pandemic could be a precursor to a more devastating second wave.

“This virus is a fierce test,” Fine said. “I fear once we let our guard down we’ll see the virus returning.”

He noted that within at-risk communities up to eight people can share a single bedroom and one bathroom. Most can’t shelter in place and have no choice but to work in jobs now deemed essential, making exposure to the coronavirus nearly unavoidable.

“There is no preventing the disease until we have a vaccine, so everyone is going to get it,” Fine said.

What’s unknown is whether hospitals have the capacity to handle a bigger outbreak. Fine believes that, so far, the country hasn’t learned enough from the first wave.

“We did not do well as a nation by any means,” he said. “We could have done better and we should have done better.”

Fred Ordoñez, a member of the Commission for Health Advocacy & Equity, which advises DOH on racial justice in health care, said reopening the economy so soon is genocide.

“Too many ‘essential workers’ that we applaud on social media are actually just poor individuals trapped into risking their lives and dying for our privilege to stay home,” Ordoñez said. “We cannot continue to keep poor people and people of color trapped into continuing to expose and infect themselves, their families, and communities.”

In response to the limited help from the state and federal government, Pawtucket and Central Falls created a community-focused command system.

“We figured out we have to take care of it ourselves,” Fine said.

A coalition of municipal and community organizations, including private companies, have created a hotline in four languages to help residents get testing, food, emotional support, medical attention, and assistance with self-isolation.

Fine wants to see a Depression-era jobs program that recruits thousands of people to help with prevention and assistance for poor and working-class residents.

Womazetta Jones, secretary of the state’s Executive Office of Health & Human Services, noted that the front lines of the crisis are made up of people of color who are suffering disproportionately from the impacts of this health crisis.

“Acknowledging the institutional racism that still exists is a first step that we have made,” Jones wrote in an email to ecoRI News.

Discussions are happening through community meetings and DOH is responding to feedback from community leaders, according to Jones. She said preventive steps are being taken to help Rhode Island’s most at-risk workers. The agency is pushing for another state stimulus package while distributing PPE and offering housing and child-care options for people who need to isolate themselves.

New, more accessible testing sites have opened near COVID-19 hot spots in Providence and Central Falls, according to Jones. She said improved public-service videos are in production, as are health-related signs and documents, some printed in 12 languages.

“We also have to address structural racism across our systems, policies, and institutions, including health care,” Jones said. “In terms of how this change should occur, we must ensure communities experiencing inequities have a prominent seat at the table.”